Beyond Accuracy: Why Guided Surgery is for Everyone

Introduction

Guided surgery isn’t a specialized technique reserved only for experts or complex cases. Recent clinical evidence suggests that guided surgery can improve consistency across practitioners. Some studies indicate that novice surgeons may achieve accuracy comparable to more experienced surgeons under controlled study conditions [1]. Complex cases may become more manageable, and many practitioners can reach proficiency relatively quickly with proper guidance and training. This article examines what current clinical evidence shows about guided implant surgery and why it is increasingly used in modern implantology.

Beyond Perfect: Why Consistency Matters

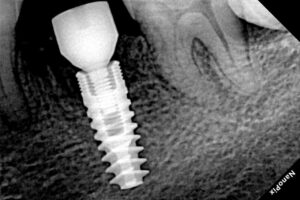

Understanding what counts as clinically relevant accuracy is key to appreciating guided surgery. Research generally considers deviations of ±1–2 mm from the planned implant position as clinically acceptable, without significantly affecting long-term outcomes.

For guided surgery, systematic reviews report mean deviations of approximately 0.74 mm at the coronal level, 1.01 mm at the apical level, and 2.34° of angular deviation [2].

Navigation-guided surgery (dynamic navigation) shows similar results in some settings. For example, in a prospective clinical trial of full‑arch, immediate-loading cases using navigation, mean angular deviation was 2.19°, and mean platform deviation was 1.17 mm (with apical deviation ~1.30 mm) [3].

The main advantage of guided surgery appears to be consistency across cases and operators, rather than achieving “perfect” placement. Freehand surgery accuracy varies widely depending on experience and case difficulty, whereas guided systems tend to produce more predictable deviations under similar conditions.

Some in vitro studies suggest that a beginner dentist using guided surgery (especially navigation) can perform with accuracy approaching that of a highly experienced clinician [1]. Nevertheless, clinical judgment – case selection, biomechanical understanding, and knowing when guidance provides an advantage – remains critical.

The Learning Curve: Rapid Improvement

Clinical and in vitro studies indicate that guided systems can shorten the learning curve:

In vitro work comparing novice vs. experienced practitioners showed that dynamic navigation significantly improved angular accuracy compared to freehand, regardless of experience [4].

In that same line of work, the time required using navigation was similar for novice and experienced surgeons, though the overall procedure took longer than freehand. [1][4]

There is some suggestion from clinical work that error stabilizes after a relatively small number of guided cases, though case complexity, planning protocols, and individual variation all matter.

By contrast, freehand placement likely requires many more cases to reach consistent, optimal outcomes. While there is no universal number, some clinical‑education literature suggests that high consistency via freehand demands substantial repetition.

Some reports indicate that anterior implants (in the front of the mouth) may reach acceptable accuracy more quickly than posterior sites, because posterior access is more challenging. However, real‑world data on how fast clinicians learn varies, and “several weeks” or “2–3 days a week” are estimates rather than precise metrics.

Failures and Complications

A meta‑analysis in BDJ Open reported a pooled early implant failure rate of 6.42% for freehand placement versus 2.25% for guided surgery, corresponding to a risk ratio of 0.29 (95% CI: 0.15–0.58; p < 0.001) [5]. This suggests a potential reduction in failure risk with guided surgery, although:

The meta-analysis included a limited number of studies, and

There was heterogeneity in designs, follow-up periods, and patient populations [5].

Some studies also indicate that guided surgery may reduce postoperative morbidity – for example, less swelling, pain, or bleeding – though these benefits appear context-dependent (patient anatomy, surgical protocol, system used) [5].

In immediate-loading, full-arch cases using navigation guidance, clinical studies report high accuracy (≈1.17 mm platform deviation, ≈1.30 mm apical deviation, ≈2.19° angular deviation) [3], with no implant failures observed in that cohort. However, these results come from a specific patient group and controlled setting, so they may not generalize to all practices.

Managing Complex Cases

Complex anatomical scenarios are an area where guided surgery often provides clear value.

In a prospective clinical trial of navigation-guided, immediate-loading, complete-arch restorations, deviations were small and consistent even in terminal or edentulous situations [3].

In fully edentulous patients, retrospective data using dynamic navigation show mean deviations around ~1.08 mm at the entry point, ~1.15 mm at the apex, and angular deviation ~2.85° [6].

Guided surgery can make certain cases more approachable for general practitioners with adequate training. Immediate implant placement and full-arch restorations, when performed with guidance, may be done safely – but that depends strongly on good planning, correct guide fabrication, and proper clinician judgment.

Consistency: The Real Guided Advantage

Guided surgery outcomes are generally more consistent across variables such as:

Surgeon experience (novice vs expert)

Case complexity

Anatomical challenges

Bone quality

In contrast, freehand surgery outcomes are more dependent on operator experience and technique. Dynamic navigation, in particular, shows that novices and experienced practitioners can achieve similar accuracy in controlled settings [1][4].

Guided surgery doesn’t remove the need for clinical judgment, but it reduces variability in technical execution. This allows practitioners to focus more on planning, decision-making, and patient-specific factors.

Fully Guided vs. Partially Guided Approaches

Different guided workflows have distinct applications and trade‑offs.

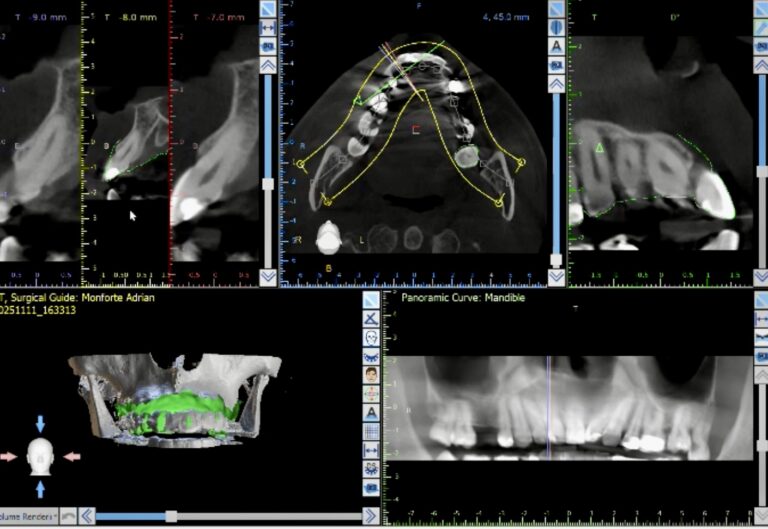

Fully Guided Surgery

Uses full surgical templates that restrict the drill throughout the osteotomy and implant insertion.

Clinical evidence suggests that fully guided workflows lead to very low deviations when properly planned and executed, and may be especially valuable in critical or anatomically demanding cases.

However, fully guided systems may be more sensitive to guide fit, drill tolerances, and patient factors (e.g., limited mouth opening).

Partially Guided Surgery

Guides only the initial osteotomy (pilot drilling), then the rest is done freehand.

Offers more flexibility for intraoperative adjustment, while maintaining a degree of precision.

May be a useful compromise in cases where full guidance is not feasible or cost-effective.

Dynamic Navigation

Real-time tracking and visualization of the drill relative to the plan.

In prospective full-arch trials, navigation produced good accuracy even in complex, immediate-loading cases [3].

Highly flexible, but requires training, calibration, and introduces its own possible sources of error.

Understanding Limitations

Guided surgery introduces potential sources of error:

Guide misfit, slippage, or movement during use

Errors in CBCT imaging, planning, or superimposition

Drill wobble or tolerance issues with sleeves and drills

Limited mouth opening that restricts guide seating or drill access

Inadequate irrigation or cooling, especially in guided protocols

Despite these, evidence suggests that, when protocols are followed properly, complication rates can remain low. However, not every patient requires guidance:

Simple single implants in ideal bone can often be placed safely and efficiently freehand.

The greatest value of guided surgery may be in complex, anatomically challenging, or prosthetically demanding cases – especially when clinicians leverage its consistency advantage.

Conclusion

Guided surgery represents a powerful and increasingly accessible tool in modern implantology. Based on current clinical evidence:

Consistency: Accuracy is more predictable across operators – including less experienced surgeons – when using guided workflows [1][2][3].

Lower Failure Rates: Early failure rates in some meta-analyses appear lower with guided surgery than freehand, though study heterogeneity tempers the strength of this conclusion [5].

Shorter Learning Curve: Guided systems, especially navigation, may reduce the number of cases required to reach stable, acceptable accuracy [1][4].

Complex Cases: Guided surgery (static or dynamic) supports safer management of challenging anatomical cases, including full-arch and edentulous treatments [3][6].

Not a Replacement for Skill: Clinical judgment, planning, and experience remain essential. Guidance helps technical execution, but doesn’t eliminate the need for sound treatment planning.

In sum, guided surgery doesn’t just aim for “perfect placement” – its real strength lies in reducing variability, improving safety, and enabling more practitioners to deliver predictable, high-quality implant therapy.

References

[1] Wang X, et al. Performance of novice versus experienced surgeons for dental implant placement with freehand, static guided and dynamic navigation approaches. Scientific Reports. 2023;13:2491. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-29701-z

[2] Abdelhay N, et al. Comparing the clinical outcomes of guided and freehand dental implant surgery: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. BDJ Open. 2021;7(1):26. doi:10.1038/s41405-021-00093-2

[3] Xing Q, et al. The Accuracy of Immediate Implantation Guided by Digital Templates and Potential Influencing Factors: A Systematic Review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2025;36(2):248-261.

[4] Pozzi A, et al. Accuracy of navigation guided implant surgery for immediate loading complete arch restorations: Prospective clinical trial. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2024 Oct;26(5):954-971. doi:10.1111/cid.13360

[5] Kundaechanont P, et al. Comparison of learning curve for anterior and posterior implant placement using dynamic computer-assisted surgical implant placement in novice and experienced operators: An in vitro trial. J Prosthet Dent. 2024. doi:10.1016/j.prosdent.2024.07.003

[6] Wang B, et al. Clinical accuracy of partially guided implant placement in edentulous patients: A computed tomography-based retrospective study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2024 Jan;35(1):31-39. doi:10.1111/clr.14191

[7] Tia M, et al. Positional Accuracy of Dental Implants Placed by Means of Computer-Aided Implant Surgery (CAIS) in Partially Edentulous Patients: A Retrospective Study. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2025;11(3):e70144. doi:10.1002/cre2.70144

[8] Nulty A, et al. A literature review on prosthetically designed guided implant placement and the factors influencing dental implant success. BDJ Open. 2024;10:22. doi:10.1038/s41405-024-00217-2

[9] Knipper A, et al. Accuracy of Dental Implant Placement with Dynamic Navigation in the Edentulous Mandible: A Randomized Prospective Clinical Study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2024;26(2):183-195. doi:10.1111/cid.13341